Review: 'This is not a Performance or a Lecture!'

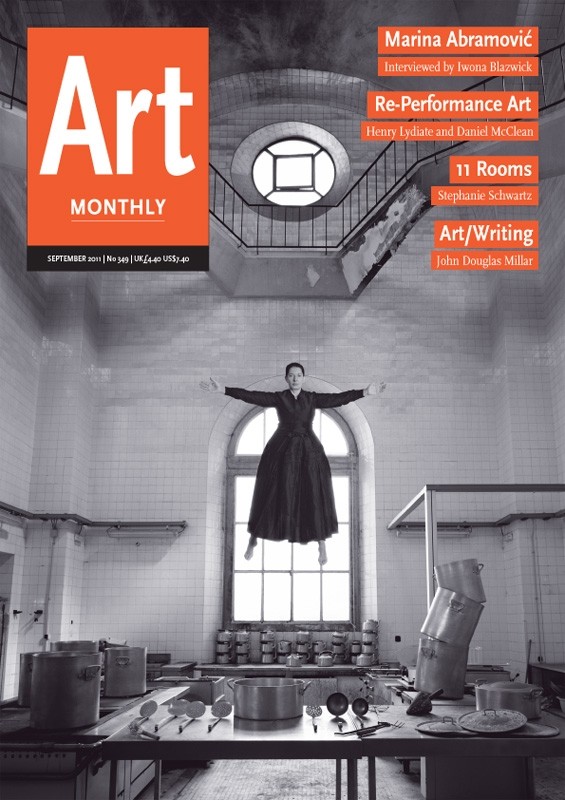

Art Monthly Issue 349, September 2011. Review by Morgan Quaintance.

‘This Is Not a Performance or a Lecture!’ was a day-long programme of site-specific and studio based performance, curated and devised by Radar: Loughborough University's innovative resident arts organisation. Instead of a day spent shuffling from neutral space to neutral space, attendants, a map and a timetable guided the collective audience across the university's prodigious grounds. Loughborough boasts the largest single site campus in the UK and use of its lecture halls, theatres and state-of-the-art sports facilities were offered to the performers.

Radar's theme, to which participating artists' were invited to respond, was based on artists’ increasing use of the performance lecture medium: a mode of address in which the tools, techniques and restrictions of official presentation are used for creative purposes.

Frank Abbott's Moose Memory, 2011, a kind of comedy routine as PowerPoint presentation, starts the day's programme at 12:30. Ushered into a small black-box theatre the audience is given stapled A4 handouts, seated and shown a series of Clipart PowerPoint slides. The professorial Abbott stands to the right of the stage, clicking through the presentation, faltering occasionally, and backtracking. A moose figures heavily in all the slides; there is a party in New York, a hunter, a car journey and, frustratingly, a narrative that won't emerge. The second part of Abbott's performance takes place outside. A woman delivers a monologue by a large tree. Drowned out by the patter of rain falling against a dozen umbrellas, nobody can hear her. Confused and slightly wet, attendees are led to the site of PiI & Galia Kollectiv's studio-based performance. Epic Sea Battle at Night: A Revolutionary Play Permeated with the Economic Thinking of Milton Friedman, is a re-enactment of the 1967 China's People's Liberation Army play Epic Sea Battle at Night. Dressed in proletariat garb, and standing in a revolutionary tableau, the group replaces the play's original dialogue with readings, delivered as a series of declaratory revolutionary statements, from Milton Friedman's Capitalism and Freedom, an evangelical celebration of neoliberal economics. The unsubtle ironies of the group's performance are initially engaging, but the 30-minute duration sends a wave of mid afternoon ennui through the audience (even performance lectures can go on for too long).

One of the pitfalls of thematically led programmes is their conceptual inflexibility. Themes help to orient audience attention towards a specific set of considerations, but sometimes these considerations foreground lesser elements of what actually takes place within the work. Robin Deacon's powerful The Argument Against the Body, a performance in five parts, wrenched the audience away from Radar's thematic line, setting them on a course towards Cartesian dualism and the consideration of the body as a present-at-hand object.

The performance takes place in Loughborough's extraordinary and unexpectedly beautiful 12x30m Badminton centre. On top of the deep azure green of the centre's clay floor, perfect white lines form a number of playing-court zones. Rows of diffused florescent tubes give the setting a kind of hyperreal glow, intensifying the solemnity of the largely empty space. The audience sits on foam gym mats placed along the width of the hall's grey concrete walls. A projector screen, microphone stand and video camera stand left to right, a metre of space separating each. It is a genuine shock when, after a section of film, Deacon's fragile naked body enters, striding across the hall to stand in front of the microphone. A monologue by Deacon has been playing in his absence, but now that it is so dramatically embodied, the perceptual join is made difficult by his seconds-late lip-syncing. What Deacon presents in The Argument Against the Body is a series of mind-body problem vignettes. Each section showcases (by his own description) 'a miniature crisis of cognition'. Scenes in which fractured, out-of-sync manifestations of Deacon's voice and body are distributed across audio-visual equipment, and are designed to fast track the audience to a state of self-conscious doubt.

Although Maurice Merleau-Ponty and others maintain consciousness is a holistic phenomenon where the body and mind work in conjunction, this has not prevented the idea of dualism enduring in some form, especially in the theory and practice of competitive sports. In the fourth section of The Argument Against the Body, Deacon extends a strip of red tape across the width of the hall and runs its length until he collapses with exhaustion. During this exercise a video interview with a Loughborough Sports Science student plays in the background. He describes fatigue (his field of interest) as ‘the reduction in the amount of force a body can produce’, a statement that exemplifies the necessary separateness with which the body must be regarded by specialists and athletes. Across Loughborough's Olympic-standard training grounds, there is a kind of athletic omnipresence that forces a reconsideration of the body, presenting it as an object to be perfected, sculpted and measured. What better setting for an investigation into the body in performance, a notion that surely provides the invisible subtitle to Radar's performance-lecture theme? At 3:00 a group of dancers moves abstractedly through Loughborough's athletic centre. The dancers follow processional instructions relayed over loudspeakers, occasionally getting things wrong on purpose. This is Ruth Proctor's Repeat, Rehearse, Replay: A Conversation,and the audience watches from a stacked array of crash mats. At 4:00, in the Gymnasium, a third incarnation of Abbott's Moose Memory features a gymnast performing across several apparatus. En route to the high bars he is shot down by an invisible arrow sent from a bow Abbott has assembled. Sound effects accompany the arrow's flight. It is pure Monty Python, but it works perfectly.

In the last performance of the day, Neil Swettenham and Michael Pinchbeck's How to Write a Play Under the Influence of Deep Trance Behaviour, the artists play Richard Foreman's surrealistic video Deep Trance Behaviour in Potatoland, 2008. It contains the line ‘understand you completely when you say: I too am always in the same place’. This final reference to the theatre of the mind, or the inescapability of a remote, unchangeable and persistent interiority, stays with me as I leave Loughborough's grounds. A return to Cartesian uncertainty is the unacknowledged, and perhaps unintentional, legacy of Radar's novel and remarkably curated programme.

I think about it during the coach ride back to Nottingham, during conversations at dinner, and during the miniature crisis of cognition that takes place late at night, when, for a brief moment, my reflection is a body brushing a set of teeth, disconcertingly detached from my mind.