Making Time

Making Time was an initiative that responded to the climate emergency, bringing the ideas of artists and art production into conversation with new material possibilities. Read more

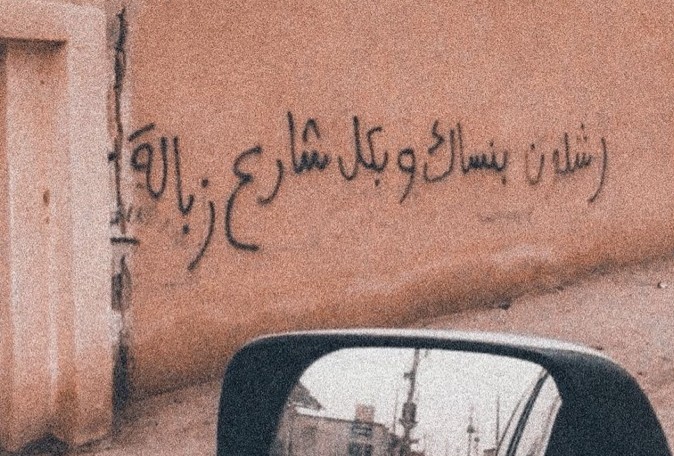

(Photo credit: Dani Admiss)

From zero-hours contracts or 8-week international exhibition runs, today, much professional art practice in the UK functions in a largely extractive and colonial manner, predicated on the exploitation of labour, mobility and resources and denying culpability in a world of ecocide, violence and contradiction. Transitioning from toxic high-energy and wasteful systems to low-carbon and circular practices in the arts could disrupt these patterns, creating lighter and more equitable circuits of exhibition, prestige, and funding but this is far from guaranteed; and as the UK continues to experience austere spending cuts, volatility and uncertainty, historic divisions in power and opportunity are likely to deepen – in the arts and elsewhere. During the Making Time period, Dani Admiss will spend time with the available departments at King’s College London, Loughborough University and University of Brighton to develop a collaboratively authored and intersectional ‘roadmap’ towards a just and circular world for art workers in the UK and beyond. Drawing on research in abolition, open-ended pedagogy, palliative care and pyschoaffective and relational practices, she will co-create a public declaration and direction for future livability.

Making Time Diaries

MARCH – APRIL

In March, the Making Time residents went on a site visit to Loughborough University. We received a tour of the Materials Department and their test facilities by Surface Interface Scientist Gary Critchlow.

There I saw a cedar tree, whose branches were bent over and were touching the ground. I later learnt that small and young trees are particularly prone to injuries caused by the weight of heavy ice and snow. I thought about the weight of climate burden that many humans and non-humans are living with. Snow, something that is characterised by its fragility and ephemerality, can cause so much lasting damage.

In March I also met with researchers at each of the Making Time partner Universities to understand more about circular economies, how they are being addressed in material cultures and in-built environments, and how we communicate this for social change.

In my conversation with Laura England, at Culture, Media & Creative Industries Education at King's College London, we spoke about sustainability, craft and economics, as well as her collaborative work with the African Hub of Sustainability. In a closed loop economy, no waste is generated; everything is shared, used or recycled. Laura told me about emerging geographies of circular economies, such as special economic zones (SEZs) and industrial parks (IPs), that enable an environment for manufacturing ‘waste streams’ and eco-innovation in countries like Kenya. Our worlds are linked by linear and wasteful economic development models, extracting raw materials and converting them into consumable products and discarding the resultant wastes into landfill/dumpsites. The environmental and social pressure of textile consumption in the West extends upstream and downstream in the production process, and a large share of used textiles are exported to Africa and Asia. What if we could hack emerging closed-loop economies that underpin capitalism, so that they are based on human rights, ecological sustainability and community wealth building?

The disconnection between artists and people-place relations was a theme also explored in my conversation with Architect, Duncan Baker-Brown at the School of Architecture, Technology and Engineering also in Brighton University. As well as being part of various international reuse and circular building projects, in 2014 Baker-Brown worked with students at Brighton University to create the UK’s first house made entirely out of waste. Waste only began to materialise in the UK during the late 19th century due to increased wealth from histories of colonisation, where people, land and resources were extracted. Duncan and I spoke about the need to relocalise forgotten knowledge about building materials and the need to mine landscapes for reusable materials instead of digging them out of the ground.

Most narratives of sustainability are about the limits of biodiversity or how to manage a physical environment in order to sustain economic activity. For many, the idea that the natural world exists to sustain and provide services to humanity, primarily as a resource supplier and waste assimilator, is a bad belief system. At the same time, the need to recognise and articulate the value inherent in our ecosystems, currently treated as ‘free’ and ‘limitless’, is clear. The construction sector plays a big role in carbon emissions and other polluting activities, and new organisations are emerging to curb extraction of natural resources by building practices and technologies that embed principles of complex closed-loop systems. Two examples Duncan shared with me are, reusable resource maps for architects that trace all the reusable bricks in a city, for instance, or material passports that track and trace the lifespans and afterlives of built materials. Each of these technologies create new relationships between buildings and the developers and architects and councils involved in their creation.

I also managed to speak with Ana Cristina Suzina, at the Institute for Media and Creative Industries at Loughborough University. Before becoming an academic, Ana worked as a journalist at a grassroots organisation in Brazil. We spoke about the co-created newspaper she worked on that was made by and for some of the most deprived communities across the country. There is power in connecting with varied communities, perspectives and voices when thinking about sustainability and climate collapse. This is our story, and we have much to learn from other outlooks.

Ana and I discussed how, in sustainability communication, there are many common terms, but this does not automatically equate to shared meanings. Ana retold a memory of a time in her field research when she was on a boat going down the Amazon river with an Indigenous Elder she was working with. She kept seeing a bird unknown to her, so she asked the Elder what the bird was called. The Elder told her that in their community the bird was a sign of good energy and that meant she was welcome there. When Ana asked the name of the bird the Elder told her their relationship to it. This example, Ana told me, illustrates how meaning often comes from our relation towards a thing.

Any collectively authored roadmap to just transition in the art and culture sector means that we need to be much more explicit about the kinds of social relations, knowledge relations and economies we choose to support, what we want to unlearn or unmake, and what worlds we want to inhabit. New tools, social and physical, will play a role in reclaiming, instituting and embedding value into these future landscapes, as well as creating enclosures that will be able to refuse harmful practices.

MAY – JUNE

On a typically dreak day in Spring, the Making Time cohort went on a field trip to the Shale bings.

In Scotland’s West Lothian, there are a series of reddish-rose coloured hills that tower out of the relatively flat ground that surrounds them. From a distance you could be forgiven for thinking they were made of red sandstone, like the rocks that can be found in central Australia. Referred to locally as bings, these unhomely crops are not natural geological formations but are actually spoil heaps from early Scottish oil production and comprise thousands of pieces of rough, pink shale. The final mines closed in the 1960s but, today, the bings are covered in verdant green foliage, with more plant species than Ben Nevis, and are remnants of this early fracking.

In 2021, in the UK, we used 63 million gallons of oil a day but back in the 19th century Scotland was one of the earliest places for oil production, albeit on a much smaller scale. The West Lothian refineries produced petrol and diesel fuel. As part of this process shale would have been blasted to 500 degrees before being thrown onto the heaps and the result was paraffin wax for lighting and candles.

As climate collapse rages on with little sign that governments will halt future licensing and consents for the exploration, development and production of fossil fuels in the UK, it is haunting to think that today many of the seemingly most unspoilt environments, have often shaped by human hands.

In 1975, as part of the Artist Placement Group (APG) project conceived by Barbara Steveni, conceptual artist John Latham was hired by Glasgow Development Agency to reimagine and find new purpose for these spoil heaps. Latham produced a ‘feasibility report’ and rather than recommending removal or reshaping, he suggested they be renamed and reconceptualised as a monument called the Venus of Niddrie.

The Niddrie Woman is a para-fictional ancestor.

A massive industrial earthwork constructed by 10,000 hands over decades.

A posthuman landscape rich with biodiversity against all odds.

A whisper connecting us to the ideas of myths and rituals long forgotten.

A prism to view extractivism’s violence that has been normalised and made invisible.

A doorway connecting life to its unintended consequences.

An exit.

JUNE – JULY

In June, as London heated up beyond normal levels, I visited the capital to speak with numerous arts organisations about how they dispose of their exhibition and programming waste, and their thoughts on circularity.

I spoke with Dr Randa Kachef, King’s College London. Kachef’s research explores the spatial distribution of littering, social behaviour issue. Kachef spoke to me about a concept they have written about called ‘polite littering’. Polite littering describes how citizens perceive themselves as non-contributory to mess, removing themselves or absolving themselves, and how this ritualised through careful placement of rubbish by bins. She spoke about how polite litters will pile up their food takeaway rubbish neatly by a bin but will then throw away a cigarette butt immediately after because disposing of the cigarette in that way is part of the ritual of smoking. She commented that those that actually know better are immune to anti-littering campaigns. We spoke about design responses, from litter leashes to extended producer responsibility.

Is polite littering unconsciously viewed as a type of protective magic?

I spoke again with Ana Cristina Suzina at Loughborough University. She tells me about a tea tradition – Guayusa tea tradition in Ecaudor. People of the tribe gather together (old and young) to tell each other about their dreams. They also perform a show and tell ceremony, if there is something they have found that they would like to talk about that expands their knowledge. It is a way of creating community and passing on knowledge. Ana describes this practice as a circular theory of knowledge. A way of facing change together. She references indigenous scholar, Ailton Krenak, who says that we are not going through revolution (one paradigm) but evolution (multiple paradigms). I tell Ana about this idea I read about to think about disposal as doorways as opposed to rubbish bins. And we speak about the need for taking time to talk about things.

From reuse schemes to digital material passports, today’s modernised waste systems are seen as efficient and sanitary, but they are also immensely unsustainable in many other areas. They distribute our waste to an undesignated ‘dead space’ feeding a ubiquitous story of consumerism and disposability.

Weaving together conversations with researchers, theoretical research, reflecting on the interviews, and returning to an ongoing theme of portals, spiral, social and solidarity economies, and the circularity of knowledge, I begin to ask, does our understanding of waste disposal in the Global North instil an expectation of disposability? Unlike bins, doorways are thresholds that unite areas that differences tend to keep apart. Sometimes called portals, they allow the passing over from inside/outside, sacred/profane, conscious/unconscious spaces prompting different behaviours and self-awareness. Inspired by 13th century Sufi poet Rumi, and writings by Arundhati Roy, Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, what would happen if we saw waste disposal less like a rubbish bin and more as a doorway?

The Breeze at Dawn (Rumi)

The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you.

Don’t go back to sleep.

You must ask for what you really want.

Don’t go back to sleep.

People are going back and forth across the doorsill

where the two worlds touch.

The door is round and open.

Don’t go back to sleep.

Bio

Dr Dani Admiss (she/her) is a British-Iranian independent curator and researcher based in Edinburgh. She uses social practices to develop projects, investigations and networks that bring together in-world experts with everyday people to voice their stories, and unlearn and reimagine narratives of science, technology and colonialism. Since 2020, she has worked on Sunlight Doesn’t Need a Pipeline, a project exploring and enacting just transition in the arts. Across 2022, a coalition of art workers, agitators, dream weavers, makers, and caregivers, co-created a bottom-up and open-source decarbonisation plan for art workers. As an outcome of this project she is currently working on the Sunlight Liberation Network, an honest, humble and humourful support and education group for climate justice and art workers. Admiss has curated projects across the UK, Europe and internationally including at the Barbican Centre, Somerset House, MAAT, Lisbon and Lisbon Architecture Triennale. She was a Stanley Picker Fellow (2020) with Stanley Picker Gallery and Kingston University. She wrote her PhD in Curatorial Practice and World- Making with an AHRC grant and is a visiting tutor at National College of Art and Design, Dublin.

Making Time was an initiative that responded to the climate emergency, bringing the ideas of artists and art production into conversation with new material possibilities. Read more